Behavioristic Theories

By Notes Vandar

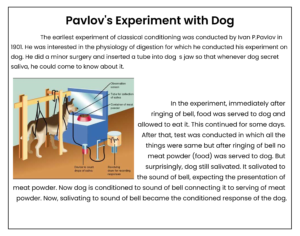

2.1 Introduction to Classical Conditioning (Pavlovian conditioning).

Pavlov (1902) started from the idea that there are some things that a dog does not need to learn. For example, dogs don’t learn to salivate whenever they see food. This reflex (response) is „hard-wired‟ into the dog. In behaviorist terms, it is an unconditioned response (i.e., a stimulus-response connection that required no learning). In behaviorist terms, we write:

Unconditioned Stimulus (Food) > Unconditioned Response (Salivate) However, when Pavlov discovered that the dogs learned to associate any object or event with food (such as the lab assistant/bell) produced the same response. Then, he realized that he had made an important scientific discovery. Thereafter, Pavlov devoted the rest of his career to studying this type of learning.

Pavlov knew that somehow, the dogs in his lab had learned to associate food with his lab assistant. This must have been learned, because at one point the dogs did not do it, and there came a point where they started, so their behavior had changed. A change in the behavior of this type must be the result of learning.

In behaviorist terms, the lab assistant was originally a neutral stimulus. It is called neutral because it produces no response. What had happened was that the neutral stimulus (the lab assistant) had become associated with an unconditioned stimulus (food).

In his experiment, Pavlov used a bell as his neutral stimulus. Whenever he gave food to his dogs, he also rang a bell. After a number of repeats of this procedure, he tried the bell on its own. As you might expect, the bell on its own now caused an increase in salivation.

So, the dog had learned an association between the bell and the food and a new behavior had been learned. Because this response was learned (or conditioned), it is called a conditioned response. The neutral stimulus has become a conditioned stimulus.

Pavlov found that for associations to be made, the two stimuli had to be presented close together

in time. He called this the law of temporal contiguity. If the time between the conditioned stimulus (bell) and unconditioned stimulus (food) is too great, then learning will not

occur.

Pavlov and his studies of classical conditioning have become famous since his early work between 1890-1930. Classical conditioning is “classical” in that it is the first systematic study of basic laws of learning / conditioning

Classical conditioning theory states that a subject can be conditioned (trained) to

respond to a neutral stimulus if the neutral stimulus is paired up with any natural stimulus

that creates the required response. By presenting both stimulus simultaneously, the subject will

unconsciously associate its current response to the neutral stimulus too.

This technique is widely used to train animals. By creating a positive stimulus and then

matching it to the neutral stimulus that needs to be taught, the trainer can modify the animal’s

behavior and get the response he is looking for after repeating the process for a given period of

time. This method is also called Pavlovian conditioning.

Three Stages of Conditioning

There are three stages of classical conditioning. At each stage the stimuli and responses are given special scientific terms:

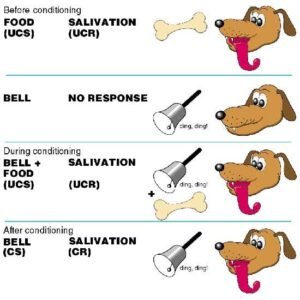

Stage 1: Before Conditioning:

In this stage, the unconditioned stimulus (UCS) produces an unconditioned response (UCR) in an organism -k|f0fLdf_. In basic terms, this means that a stimulus in the environment has produced a behavior / response which is unlearned (i.e., unconditioned) and therefore is a natural response which has not been taught. In this respect, no new behavior has been learned. For example, a stomach virus (UCS) would produce a response of nausea (UCR). In another example, a perfume (UCS) could create a response of happiness or desire (UCR).

This stage also involves another stimulus which has no effect on a person and is called the neutral stimulus (NS). The NS could be a person, object, place, etc. The neutral stimulus in classical conditioning does not produce a response until it is paired with the unconditioned stimulus.

Stage 2: During Conditioning:

During this stage a stimulus which produces no response (i.e., neutral) is associated with the unconditioned stimulus at which point it now becomes known as the conditioned stimulus (CS).For example, a stomach virus (UCS) might be associated with eating a certain food such as

chocolate (CS). Also, perfume (UCS) might be associated with a specific person (CS). Often during this stage, the UCS must be associated with the CS on a number of occasions, or trials, for learning to take place. However, one trail learning can happen on certain occasions

when it is not necessary for an association to be strengthened over time (such as being sick after food poisoning or drinking too much alcohol).

Stage 3: After Conditioning:

Now the conditioned stimulus (CS) has been associated with the unconditioned stimulus (UCS) to create a new conditioned response (CR). For example, a person (CS) who has been associated with nice perfume (UCS) is now found attractive (CR). Also, chocolate (CS) which was eaten before a person was sick with a virus (UCS) now produces a response of nausea (CR).

Key Principles/Characteristics of Classical Conditioning

Behaviorists have described a number of different phenomena associated with classical conditioning. Some of these elements involve the initial establishment of the response while others describe the disappearance of a response. These elements are important in understanding

the classical conditioning process. Let’s take a closer look at five (or six) key principles of classical conditioning:

1. Acquisition: Acquisition is the initial stage of learning when a response is first established and gradually strengthened. During the acquisition phase of classical conditioning, a neutral stimulus is repeatedly paired with an unconditioned stimulus. As you may recall, an

unconditioned stimulus is something that naturally and automatically triggers a response without any learning. After an association is made, the subject will begin to emit a behavior in response to the previously neutral stimulus, which is now known as a conditioned stimulus. It is at this point that we can say that the response has been acquired. For example, imagine that you are conditioning a dog to salivate in response to the sound of a bell. You repeatedly pair the presentation of food with the sound of the bell. You can say the

response has been acquired as soon as the dog begins to salivate in response to the bell tone. Once the response has been established, you can gradually reinforce the salivation response to make sure the behavior is well learned.

2. Stimulus Generalization: In the conditioning process, stimulus generalization is the tendency for the conditioned stimulus to evoke similar responses after the response has been conditioned. For example, if a child has been conditioned to fear with a white rabbit, it will

also fear with white objects such as a white toy rat. In the classic Little Albert experiment, researchers John B. Watson and Rayner conditioned a little boy to fear a white rat. The researchers observed that the boy experienced stimulus generalization by showing

fear in response to similar stimuli including a dog, a rabbit, a fur coat, a white Santa Claus beard, and even Watson’s own hair. Instead of distinguishing between the fear object and similar stimuli, the little boy became fearful of objects that were similar in appearance to the

white rat.

3. Stimulus Discrimination: Discrimination is the ability to differentiate between a conditioned stimulus and other stimuli that have not been paired with an unconditioned stimulus. For example, if a bell tone were the conditioned stimulus, discrimination would involve being able to tell the difference between the bell tone and other similar sounds. Because the subject is able to distinguish between these stimuli, he or she will only respond when the conditioned stimulus is presented.

4. Extinction: In classical conditioning, when a conditioned stimulus is presented alone without an unconditioned stimulus, the conditioned response will eventually cease (stop). For example, in Pavlov’s classic experiment, a dog was conditioned to salivate to the sound of a bell. When the bell was repeatedly presented without the presentation of food, the salivation response eventually became extinct.

5. Inhibition: Inhibition is the opposite of facilitation and refers to a mental state in which there is interference in the conditioned response (CR). It is the cause of extinction. It is claimed that the inhibition is not a temporary process. There are a number of inhibitions (causes of extinction/interferences for (CR).

a) Conditioned inhibition: It is the process the inhibition of the CR is permanent. The long term inhibition prevents for the spontaneous recovery.

b) External inhibition: It is the process of interference caused by external stimulus. In Pavlov’s experiment a noisy truck passed by outside Pavlov’s lab. His interpretation was that such an unusual stimulus distract the dog from the CS and hence cause a decreased flow of conditioned saliva.

d) Latent inhibition: The basic idea of latent inhibition is that it is often easier to learn something new than to unlearn something familiar. If something is already known, it interferes to learn differently because the earlier learning interferes later learning. A familiar stimulus takes longer to acquire meaning (as a signal or conditioned stimulus) than a new stimulus. It is also understood as L1 effect.

e) Disinhibition: A novel situation or stimulus can make an extinguished CS effective again. This is known as disinhibition.

6. Spontaneous Recovery: It refers to the re-emergence of a previously extinguished conditioned response after a delay. Sometimes, the CR suddenly reappears even after then link between CS and UCS has been broken down, or to put in another words, the organism has stopped eliciting CR in response to CS. In Pavlov‟s experiment, when the dog had completely stopped eliciting CR (Saliva) in response to CS (bell sound), the dog still responded with saliva at the sound of the bell. This sudden reappearance of saliva (CR) was referred as „spontaneous recovery‟ by Pavlov. This principle can be used to explain why “cured” alcohol and drug addicts again “relapse to addiction”. When the cured addicts confront with the substance, the irresistible urge to use the substance again may resurface because of the strong connection to the drug previously. This can be termed as Spontaneous Recovery.

7. Latency: The time difference between the conditioned stimulus and the unconditioned stimulus is referred to as latency. First of all, note that the conditioned stimulus must come first. For example, if Pavlov always sounded the tone after the dog got meat powder, the tone, in the absence of the meat powder, would signal was that the dog somehow missed getting it‟s meet powder so, in fact, it might as well not salivate. Given that the conditioned stimulus does precede the unconditioned stimulus, the general rule of thumb is that the shorter the latency the more likely it is that the conditioning will occur

Implications (of Classical conditioning theory) in teaching and learning

This theory can help teachers and learners for teaching learning development in the following ways:

- The theory implies one must be able to practice and master a task effectively before going on another one (Pp6f l;s]/ dfq csf{] l;Sg ;lsG5). This means that a student needs to be able to respond to a particular stimulus (information) before he/she can be associated with a new

one. - Teachers should know how to motivate their students to learn. They should be resourceful with various strategies that can enhance effective participation of the students in the teaching learning activities.

- Most of the emotional responses can be learned through classical conditioning (classical condition sf] dfWod af6 ;+a]ufTds l;sfO l;Sg ;lsG5) A negative or positive response comes through the stimulus being paired with. For example, providing the necessary school material for primary school pupils will develop good feelings about school and learning in them, while punishment will discourage them from attending the school.

- The Learners develop hatred towards Maths due to teacher’s behavior (lzIfssf]Jojxf/n]ubf{ s’g} ljifo k|lt g}3[0ff hfUg ;sS5) But, a good method and loving behavior of the teacher can bring desirable impacts upon the Learners. The Learners may like the boring subject because of teacher’s role.

- In teaching audio-visual aids ->Ao b [io ;fdu|L/;xof]uL ;fdu|L sf] e”ldsf_ role is very vital. When a teacher want to teach a cat. He or she shows the picture of the cat along with the spellings. When teacher shows picture at the same time, he or she spell out the spellings, after a while when only picture is shown, and the Learners spell the word cat.

- Emphasis on behavior: Students should be active respondents to learning, and in the learning process. They should be given an opportunity to actually behave or demonstrate learning. Secondly students should be assessed by observing behaviour, we can never

assume that students are learning unless we can observe that behavior is changing. - Drill and practice: the repetition of stimulus response habits can strengthen those habits. For example, some believe that the best way to improve reading is to have students read more and more. “Practice is important.

- To break a bad habit, a learner must replace one S-R connection with another one .In order to break habits, that teacher needs to lead an individual to make a new response to this same old stimulus.

- Link learning with positive emotions. Arrange repeated pairing of positive feelings with certain kinds of learning, especially subjects that are anxiety provoking.

- Teach students to generalize and discriminate appropriately.

2.2 Operant Conditioning (Skinnerian Conditioning).

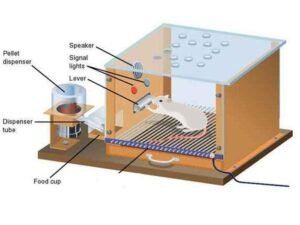

Basic process of operant. conditioning and experiment on rat Perhaps the most important of the behaviourists was Burrhus Frederic Skinner. He is more commonly known as B.F. Skinner. His views were slightly less extreme than those of Watson (1913). Skinner believed that we have such a thing as a mind, but that it is simply more productive to study observable behavior rather than internal mental even

Skinner believed that classical conditioning was too simplistic to be used to describe something as complex as human behavior. Operant conditioning, in his opinion, better described human behavior since it examined that causes and effects of intentional behavior. To implement his empirical approach, Skinner invented the operant conditioning chamber, or “Skinner Box”, in which subjects such as pigeons and rats were isolated and could be exposed to carefully controlled stimuli.

Operant Conditioning deals with operant – intentional actions that have an effect on the surrounding environment. Skinner set out to identify the processes which made certain operant behaviors more or less likely to occur.

Skinner, first time, got the idea that most of the responses could not be attributed to the known stimuli. He defined two types of responses—the one “elicited” by known stimuli which he called as “respondent behaviour” and the other “emitted” by the unknown stimuli which he

called as “operant behaviour”.

Operant conditioning is a type of learning where behavior is controlled by consequences. Key concepts in operant conditioning are positive reinforcement, negative reinforcement, positive punishment and negative punishment. It (sometimes referred to as instrumental conditioning) is a method of learning that occurs through rewards and punishments for behavior. Through operant conditioning, an association is made between a behavior and a consequence for that behavior. For example, when a lab rat presses a blue button, he receives a food pellet as a reward, but when he presses the red button he receives a mild electric shock. As a result, he learns to press the blue button but avoid the red button.

His work was based on Thorndike’s (1905) law of effect. Skinner introduced a new term into the Law of Effect – Reinforcement. Behavior which is reinforced tends to be repeated (i.e., strengthened); behavior which is not reinforced tends to die out-or be extinguished (i.e., weakened).

Skinner (1948) studied operant conditioning by conducting experiments using animals. But, his first experiment was done upon rat. He placed the rat in a box (called ‘Skinner Box’) which was similar to Thorndike’s ‘puzzle box’.

Experiments

B. F. Skinner used a Skinner box to study operant learning. The box contains a bar or key that the organism can press to receive food and water, and a device that records the organism’s responses. The most basic of Skinner’s experiments was quite similar to Thorndike’s research with cats. A rat placed in the chamber reacted as one might expect, scurrying about the box and sniffing and clawing at the floor and walls. Eventually the rat chanced upon a lever, which it pressed to release pellets of food. The next time around, the rat took a little less

time to press the lever, and on successive trials, the time it took to press the lever became shorter and shorter. Soon the rat was pressing the lever as fast as it could eat the food that appeared. As predicted by the law of effect, the rat had learned to repeat the action that brought about the food and cease the actions that did not.

B.F. Skinner (1938) coined the term operant conditioning; it means roughly changing of behavior by the use of reinforcement which is given after the desired response. We can all think of examples of how our own behavior has been affected by reinforcers and punishers. As a child you probably tried out a number of behaviors and learned from their consequences. For example, if when you were younger you tried smoking at school, and the chief consequence was that you got in with the crowd you always wanted to hang out with, you would have been positively reinforced (i.e., rewarded) and would be likely to repeat the behavior.

If, however, the main consequence was that you were caught, caned, suspended from school and your parents became involved you would most certainly have been punished, and you would consequently be much less likely to smoke now.

Types of Reinforcement

In operant conditioning, there are two different types of reinforcement. Both of these forms of reinforcement influence behavior, but they do so in different ways.

Positive Reinforcement

In operant conditioning, positive reinforcement involves the addition of a reinforcing stimulus following a behavior that makes it more likely that the behavior will occur again in the future. When a favorable outcome, event, or reward occurs after an action, that particular response or behavior will be strengthened. One of the easiest ways to remember positive reinforcement is to think of it as something being added.

By thinking of it in these terms, you may find it easier to identify real-world examples of positive

reinforcement.

Sometimes positive reinforcement occurs quite naturally. For example, when you hold the door open for someone you might receive praise and a thank you. That affirmation serves as positive reinforcement and may make it more likely that you will hold the door open for people again in the future.

In other cases, someone might choose to use positive reinforcement very deliberately in order to train and maintain a specific behavior. An animal trainer, for example, might reward a dog with a treat every time the animal shakes the trainer’s hand.

Skinner showed how positive reinforcement worked by placing a hungry rat in his Skinner box. The box contained a lever on the side, and as the rat moved about the box, it would accidentally knock the lever. Immediately it did so, and a food pellet would drop into a container next to the lever.

The rats quickly learned to go straight to the lever after a few times of being put in the box. The consequence of receiving food if they pressed the lever ensured that they would repeat the action again and again.

Positive reinforcement strengthens a behavior by providing a consequence an individual finds rewarding. For example, if your teacher gives you £5 each time you complete your homework (i.e., a reward) you will be more likely to repeat this behavior in the future, thus strengthening the behavior of completing your homework.

Negative Reinforcement

Negative reinforcement is a term described by B. F. Skinner in his theory of operant conditioning. In negative reinforcement, a response or behavior is strengthened by stopping, removing, or avoiding a negative outcome or aversive stimulus.

Negative reinforcement occurs when something already present is removed (taken away) as a result of a behavior and the behavior that led to this removal will increase in the future because it created a favorable outcome.

Aversive stimuli tend to involve some type of discomfort, either physical or psychological. Behaviors are negatively reinforced when they allow you to escape from aversive stimuli that are already present or allow you to completely avoid the aversive stimuli before they happen.

Deciding to take an antacid before you indulge in a spicy meal is an example of negative reinforcement. You engage in an action in order to avoid a negative result.

One of the best ways to remember negative reinforcement is to think of it as something being subtracted from the situation. When you look at it in this way, it may be easier to identify examples of negative reinforcement in the real-world.

Examples of Negative Reinforcement

Example: Thomas has wet hands after washing them. He rubs them in the towel and the water is now removed from them. He knows that every time he doesn’t want his hands to remain wet he can use a towel to get rid of the water. He now uses a towel every time he wants to remove the water from his hands.

For example, if you do not complete your homework, you give your teacher £5. You will complete your homework to avoid paying £5, thus strengthening the behavior of completing your homework.

Skinner showed how negative reinforcement worked by placing a rat in his Skinner box and then subjecting it to an unpleasant electric current which caused it some discomfort. As the rat moved about the box it would accidentally knock the lever. Immediately it did so the electric current would be switched off. The rats quickly learned to go straight to the lever after a few times of being put in

the box. The consequence of escaping the electric current ensured that they would repeat the action again and again.

In fact, Skinner even taught the rats to avoid the electric current by turning on a light just before the electric current came on. The rats soon learned to press the lever when the light came on because they knew that this would stop the electric current being switched on.

These two learned responses are known as Escape Learning and Avoidance Learning. The removal of an unpleasant reinforce can also strengthen behavior. This is known as negative reinforcement because it is the removal of an adverse stimulus which is ‘rewarding’ to the animal or person. Negative reinforcement strengthens behavior because it stops or removes an unpleasant experience.

Punishment (weakens behavior)

Punishment is defined as the opposite of reinforcement since it is designed to weaken or eliminate a response rather than increase it. It is an aversive event that decreases the behavior that it follows.

Like reinforcement, punishment can work either by directly applying an unpleasant stimulus like a shock after a response or by removing a potentially rewarding stimulus, for instance, deducting someone’s pocket money to punish undesirable behavior.

Note: It is not always easy to distinguish between punishment and negative reinforcement.

There are many problems with using punishment, such as:

- Punished behavior is not forgotten, it’s suppressed – behavior returns when punishment is no

longer present. - Causes increased aggression – shows that aggression is a way to cope with problems.

- Creates fear that can generalize to undesirable behaviors, e.g., fear of school.

- Does not necessarily guide toward desired behavior – reinforcement tells you what to do,

punishment only tells you what not to do.

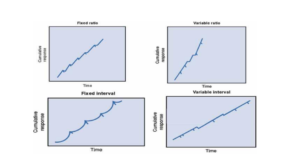

Schedules of Reinforcement

Skinner also found that when and how often behaviors were reinforced played a role in the speed and strength of acquisition. He identified several different schedules of reinforcement:

1. Continuous reinforcement involves delivery a reinforcement every time a response occurs. Learning tends to occur relatively quickly, yet the response rate is quite low. Extinction also occurs very quickly once reinforcement is halted.

2. Fixed-ratio schedules are a type of partial reinforcement. Responses are reinforced only after a specific number of responses have occurred. This typically leads to a fairly steady response rate.

3. Fixed-interval schedules are another form of partial reinforcement. Reinforcement occurs only after a certain interval of time has elapsed. Response rates remain fairly steady and start to increase as the reinforcement time draws near, but slow immediately after the reinforcement has been delivered.

4. Variable-ratio schedules are also a type of partial reinforcement that involve reinforcing behavior after a varied number of responses. This leads to both a high response rate and slow extinction rates.

5. Variable-interval schedules are the final form of partial reinforcement Skinner described. This schedule involves delivering reinforcement after a variable amount of time has elapsed. This also tends to lead to a fast response rate and slow extinction rate.

Behavior Shaping

The concept of behavior shaping was first developed and used by B.F Skinner as an application of learning behaviors through reinforcement. Behavior shaping is the process of reinforcing behaviors that are closer to the target behavior (expected behavior), also known as successive approximations.

The theory involves reinforcing behavior that are successively closer and closer to the approximations of the desired, or targeted, behavior. The process of shaping is vital because it’s not always likely that an organism should display the exact target behavior spontaneously.

However, by reinforcing the behavior that is closer and closer to the desired behavior, the required behavior can be taught/learned. The step by step procedure of reinforcing different behaviors until the target behavior is achieved is called Successive Approximations.

One of the first experiments conducted by B.F Skinner on shaping involved teaching pigeons how to bowl, where the pigeons were gradually taught to sideswipe the ball with its beak down the alley towards the pins.

In his experiment where he taught a rat how to press the lever for food, it wasn’t a sudden spontaneous behavior rat performed out of guess. The target behavior for the rat was to press the lever, in which case, it would be rewarded with food. But, of course, the rat wasn’t going to

spontaneously press the lever. So, the trainer, initially, even gave rewards to crude (simple/rough/ basic) approximations of the target behavior. For example, even a single step taken in the right direction was reinforced. Then, another step was reinforced, and likewise

Skinner would reward the rat for standing on its hind legs, then even the slightest touch on the lever was rewarded, until the rat finally pressed the lever.

The crucial aspect of this procedure is to only reward new behaviors that are closer to the targeted behavior. For instance, in the experiment with the rat, once the rat touched the lever, it wasn’t rewarded for standing on its hind legs. And, when the targeted behavior is achieved, successive approximations leading towards the targeted behavior weren’t rewarded anymore. In this way, shaping uses principles of operant conditioning to train a subject to learn a behavior by reinforcing proper behaviors and discouraging unwanted behaviors.

Steps involved in the process of Shaping

The following steps are involved in behavior shaping:

- For starters, reinforce any behavior that is even remotely close to the desired, target behavior.

- Next step, reinforce the behavior that is closer to the target behavior. Also, you shouldn’t reinforce the previous behavior.

- Keep reinforcing the responses/behaviors that resembles the target behavior even more closely. Continue reinforcing the successive approximations until the target behavior is achieved.

- Once the target behavior is achieved, only reinforce the final response.

Educational Implications or Significance of Operant Conditioning:

1. Successive approximation: The theory suggests the great potentiality of the shaping procedure for behavior modification. Operant conditioning can be used for shaping behavior of children by appropriate use of reinforcement or rewards. Behavior can be shaped through successive approximation in terms of small steps. Successive approximation is a process which means that complicated behavior patterns are learned gradually through successive steps which are rewarding for the learner. Every successful step of the child must be rewarded by the teacher.

2. Eliminating negative behavior through extinction: When a learned response is repeated without reinforcement, the strength of the tendency to perform that response undergoes a progressive decrease. Extinction procedures can be successfully used by the class-room teacher in eliminating negative behavior of students.

3. Reinforcement: Operant conditioning has valuable implications for reinforcement techniques in the classroom. The schools can use the principles of operant conditioning to eliminate the element of fear from school atmosphere by using positive reinforcement. Positive reinforcement is perhaps the most widely used behavioral technique in the school setting. This technique simply involves providing a reward for positive behavior. The reward can be a high grade, a pen, a smile, a verbal compliment. The principle underlying positive reinforcement is that the tendency to repeat a response to a given stimulus will be strengthened as the response is positively rewarded.

4. Behavior modification/shaping: Shaping may be used as a successful technique for making individual learn difficult and complex behavior. Operant conditioning technique also implies the use of behavior modification programmed to shape desirable behavior

and to eliminate undesirable behavior. a teacher needs to identify the student’s strengths and weaknesses around a specific skill, and then break the skill into a series of steps that lead a child toward that target. If the targeted skill is being able to write with a pencil, a child might have difficulty holding a pencil. An appropriate assistive stepwise strategy might start with the teacher placing her hand over the child’s hand, demonstrating to the child the correct pencil grasp. Once the child achieves this step, she is rewarded, and the next step is undertaken.

5. Basis for programmed instruction: The theory provides the basis for programmed instruction. Programmed instruction is a kind of learning experience in which a programmed takes the place of tutor for the students and leads him through a set of specified behaviors. The principles originating from operant conditioning have revolutionized the training and learning programmed. Consequently, mechanical learning in the form of teaching machines and computer-assisted instructions have replaced usual classroom instructions. The use of programmed material in the form of a book or machine makes provision for immediate reinforcement.

6. Behavior therapy: Managing Problem Behavior: Two types of behavior is seen in the classroom viz undesired behavior and problematic behavior. Operant conditioning is a behavior therapy technique that shape students’ behavior. For this teacher should admit

positive contingencies like praise, encouragement etc. for learning. One should not admit negative contingencies. Example punishment (student will run away from the dull and dreary classes – escape stimulation.

Operant Conditioning Summary

Looking at Skinner’s classic studies on pigeons’ / rat’s behavior we can identify some of the major assumptions of the behaviorist approach.

• Psychology should be seen as a science, to be studied in a scientific manner. Skinner’s study of behavior in rats was conducted under carefully controlled laboratory conditions.

• Behaviorism is primarily concerned with observable behavior, as opposed to internal events like thinking and emotion. Note that Skinner did not say that the rats learned to press a lever because they wanted food. He instead concentrated on describing the easily observed behavior that the rats acquired.

• The major influence on human behavior is learning from our environment. In the Skinner study, because food followed a particular behavior the rats learned to repeat that behavior, e.g., operant conditioning.

• There is little difference between the learning that takes place in humans and that in other animals. Therefore research (e.g., operant conditioning) can be carried out on animals (Rats / Pigeons) as well as on humans. Skinner proposed that the way humans learn behavior is much the same as the way the rats learned to press a lever.

So, if your layperson’s idea of psychology has always been of people in laboratories wearing white coats and watching hapless rats try to negotiate mazes in order to get to their dinner, then you are probably thinking of behavioral psychology.

Behaviorism and its offshoots tend to be among the most scientific of the psychological perspectives. The emphasis of behavioral psychology is on how we learn to behave in certain ways. We are all constantly learning new behaviors and how to modify our existing behavior. Behavioral psychology is the psychological approach that focuses on how this learning takes place.

2.3 Connectionism (Thorndike’s Theory of Learning).

Connectionism, developed by Edward Thorndike, is one of the earliest theories of learning. It is based on the idea that learning is the result of forming connections or associations between stimuli and responses. Thorndike believed that learning is a mechanical process, where behavior is influenced by the strengthening or weakening of these associations, and his theory laid the foundation for modern behaviorist perspectives.

Key Concepts of Thorndike’s Connectionism:

- Stimulus-Response Bonds (S-R Bonds):

- Learning occurs when a specific stimulus (S) becomes associated with a specific response (R). These connections, or bonds, form the basis of learning. The stronger the bond, the more likely the response will follow the stimulus in future situations.

- Trial and Error Learning:

- Thorndike believed that learning happens through a process of trial and error. When learners encounter a new situation, they try different responses until they find one that leads to a satisfying outcome. Through repeated attempts, successful responses are reinforced, while unsuccessful ones are weakened.

- Example: A cat trying to escape from a puzzle box pulls on different levers until one opens the door. Over time, it learns the correct lever to pull and ignores the wrong actions.

- Laws of Learning:

- Thorndike proposed three primary laws of learning, as discussed earlier:

- Law of Readiness: Learners must be ready or prepared to learn for the learning process to be effective.

- Law of Exercise: Repeated use of connections strengthens them, while disuse weakens them.

- Law of Effect: Actions that produce satisfying outcomes are more likely to be repeated, while those that produce discomfort are less likely to be repeated.

- Thorndike proposed three primary laws of learning, as discussed earlier:

- Incremental Learning:

- Learning, according to Thorndike, is gradual. It doesn’t happen in an all-or-nothing manner but occurs incrementally through small steps, where the connections are gradually strengthened with each successful experience.

- Connectionism as a Mechanistic Theory:

- Thorndike’s theory views the mind as a machine that operates through the formation and strengthening of stimulus-response bonds. Learning, in this context, is automatic and based on mechanical associations rather than conscious thought processes or insight.

- Reinforcement:

- Reinforcement is critical in Thorndike’s theory. Positive reinforcement strengthens the connection between a stimulus and a correct response, making it more likely to be repeated. Negative reinforcement weakens the connection, reducing the likelihood of the incorrect response being repeated.

Example of Connectionism in Action:

Consider a student learning to ride a bicycle. Initially, the student tries various techniques to balance, and through trial and error, they gradually learn the correct movements that lead to balance and control. As they practice, the successful behaviors are reinforced, and over time, they become more proficient, learning to ride the bicycle smoothly.

Influence of Thorndike’s Connectionism:

Thorndike’s connectionism theory has had a profound impact on educational practices, behaviorism, and the study of learning. It highlights the importance of practice, reinforcement, and gradual improvement. His work paved the way for other behaviorists like B.F. Skinner, who developed the concept of operant conditioning, expanding on the ideas of stimulus-response relationships and reinforcement.

2.3.1 Basic process of conditioning (process of trial and error) and experiment on cat.

The basic process of conditioning, especially in the context of trial and error learning, is a fundamental concept in behavioral psychology. This concept was explored through various experiments, including the famous experiment on a cat by Edward Thorndike.

1. Basic Process of Conditioning

Conditioning refers to the process of learning associations between behaviors and consequences. Two major types of conditioning are classical conditioning and operant conditioning:

- Classical Conditioning (Pavlov): Involves learning through association, where a neutral stimulus becomes associated with a meaningful stimulus, eliciting a similar response (e.g., Pavlov’s dog salivating at the sound of a bell).

- Operant Conditioning (Skinner): Involves learning through the consequences of behavior. Rewards reinforce behavior, while punishments decrease it.

2. Trial and Error Learning

Trial and error is a method of learning in which an individual attempts different solutions to a problem until they succeed. This process is fundamental to operant conditioning, where behavior is shaped by the outcomes or consequences.

3. Thorndike’s Experiment on Cats (Puzzle Box)

The most famous experiment related to trial and error learning was conducted by Edward Thorndike in the late 19th century. Thorndike was interested in understanding how animals learn and proposed the Law of Effect, which later became a foundation for operant conditioning.

Experiment on the Cat (Puzzle Box):

- Setup: Thorndike placed hungry cats inside a “puzzle box,” a small cage with a lever or string that would open the door if manipulated in the right way. Outside the box was food to motivate the cat.

- Process: The cat would move around the box, trying different actions (scratching, biting, pushing) to escape and reach the food. Initially, the cat’s attempts were random, and it accidentally triggered the lever, opening the door.

- Trial and Error Learning: Over repeated trials, the cat learned to associate the lever with escape and food. Gradually, the time taken to press the lever decreased, showing that the cat was learning from its mistakes.

- Conclusion: Thorndike concluded that animals learn through a process of trial and error, and behaviors that lead to satisfying outcomes (e.g., getting food) are more likely to be repeated. This led to the formulation of the Law of Effect:Law of Effect: Behaviors followed by positive outcomes are strengthened, while behaviors followed by negative outcomes are weakened.

Significance of Thorndike’s Experiment:

- It demonstrated that learning in animals (and humans) often occurs through trial and error, where successful actions are reinforced.

- It laid the groundwork for B.F. Skinner’s later work on operant conditioning, which formalized the concepts of reinforcement (positive and negative) and punishment in learning.

2.3.2 primary laws of learning: law of readiness, law of exercise and law of effect.

The primary laws of learning proposed by Edward Thorndike form the core of his theory of learning, which is based on the idea of connections between stimuli and responses. The three fundamental laws of learning are:

1. Law of Readiness:

- Definition: Learning is more effective when the learner is ready to act. Readiness refers to the learner’s mental, emotional, and physical preparedness to engage in a learning task. When a person is in a state of readiness, they are more willing and able to perform a task.

- Implication: If a person is not ready, forcing them to learn can lead to frustration, which may hinder the learning process.

- Example: A student who is motivated to learn and has the necessary pre-requisite knowledge will engage better in a lesson than a student who is uninterested or unprepared.

2. Law of Exercise:

- Definition: Repetition strengthens the connection between stimulus and response, while lack of use weakens it. The more a particular action is practiced, the more likely it is to be performed effectively.

- Implication: Consistent practice is key to mastering a skill. Lack of practice will weaken the learned association.

- Example: A person learning to play the piano improves through regular practice, while someone who stops practicing will lose proficiency over time.

3. Law of Effect:

- Definition: Responses followed by positive consequences (satisfaction) are more likely to be repeated, while responses followed by negative consequences (discomfort) are less likely to be repeated. The consequences of an action determine whether it will be learned and repeated.

- Implication: Reinforcement (positive or negative) plays a critical role in the learning process. Rewarding good behavior increases the likelihood of that behavior being repeated, while punishing undesired behavior decreases its occurrence.

- Example: A child who receives praise for solving a math problem correctly is more likely to engage in solving math problems in the future, while one who is scolded for making mistakes may avoid the activity.

These laws emphasize the importance of motivation (readiness), practice (exercise), and consequences (effect) in learning. Thorndike’s work laid the foundation for behavioral theories and contributed significantly to educational psychology.

2.3.3 Educational implications.

The educational implications of Thorndike’s laws of learning (readiness, exercise, and effect) have a profound influence on teaching and classroom practices. By applying these principles, educators can enhance the learning process and create an environment that fosters effective learning. Here’s how each law impacts education:

1. Implications of the Law of Readiness:

- Personalized Learning: Students should be mentally and emotionally ready before engaging in a learning activity. This means teachers need to ensure that learners have the required background knowledge and are motivated to learn.

- Pre-assessment: Educators should assess students’ prior knowledge and preparedness before introducing new concepts. This helps avoid frustration and ensures students are ready to grasp new material.

- Creating Interest: Teachers should spark curiosity and motivation in students, making the learning process enjoyable and meaningful. Engaging lessons, relevant topics, and a supportive environment encourage readiness.

- Developmentally Appropriate Lessons: Instruction should match the student’s cognitive, emotional, and developmental stage. Overly difficult or overly simple tasks can demotivate learners who are either unprepared or too advanced for the material.

2. Implications of the Law of Exercise:

- Repetition and Practice: Skills and knowledge are reinforced through repeated practice. Teachers need to provide ample opportunities for students to practice what they learn. Frequent review sessions, homework, and in-class exercises help strengthen learning connections.

- Skill Mastery: Mastery learning techniques, where students practice a skill until they achieve a high level of competence, align with this law. Continuous feedback and correction during practice ensure long-term retention.

- Consistent Learning Routines: Classroom routines and structured repetition (e.g., daily drills, quizzes) support learning, especially for foundational skills like reading and mathematics.

- Hands-On Learning: Encouraging students to actively engage with materials or subjects through repeated, real-world applications (e.g., lab work, experiments, or problem-solving tasks) enhances retention.

3. Implications of the Law of Effect:

- Positive Reinforcement: Positive outcomes, like praise, rewards, or success, motivate students to continue learning and improve their performance. This law highlights the importance of encouragement and recognition for achievements in learning.

- Constructive Feedback: Teachers should give timely and constructive feedback to guide students. If students receive negative feedback, it should be done in a way that encourages improvement rather than discouragement.

- Motivational Strategies: Teachers should create a positive and supportive learning environment where students feel safe to make mistakes and learn from them. Rewarding correct responses with praise, grades, or rewards helps reinforce learning.

- Punishment and Behavior: Punishing undesirable behaviors may reduce their occurrence, but too much negative reinforcement can discourage learning. Educators need to balance consequences with encouragement to maintain a positive classroom atmosphere.

General Educational Implications of Thorndike’s Theories:

- Lesson Planning:

- Teachers should structure lessons based on students’ readiness, ensuring they are prepared for new learning experiences. The gradual introduction of new concepts and sufficient practice reinforces learning.

- Differentiation:

- Teachers must adapt their methods to cater to students with different levels of readiness and understanding. Tailoring instruction based on individual needs ensures that all students benefit from the lesson.

- Classroom Management:

- Positive reinforcement is crucial for maintaining good classroom behavior and engagement. By recognizing and rewarding desirable behavior, teachers can create a positive learning environment.

- Active Learning:

- Providing students with active learning experiences, such as problem-solving tasks, role-playing, or group work, supports the practical application of the law of exercise and the law of effect.

- Building Confidence:

- Educators should encourage small successes early in the learning process to build students’ confidence, ensuring that their experiences with learning are positive and satisfying.

Overall, Thorndike’s laws of learning emphasize the importance of preparation, practice, and reinforcement in the educational process. Applying these principles helps create a structured, engaging, and supportive learning environment where students are motivated and able to succeed.

2.4 Applications of integrated approaches to learning